We should all aspire to say three words. If you can say these three words – and mean them – you will have arrived at a point in your life that you most want to be. I came across these three words in The Little House on the Prairie books. The nine volumes are beautifully written, evoking in rich detail, family life in the west in the nineteenth century.

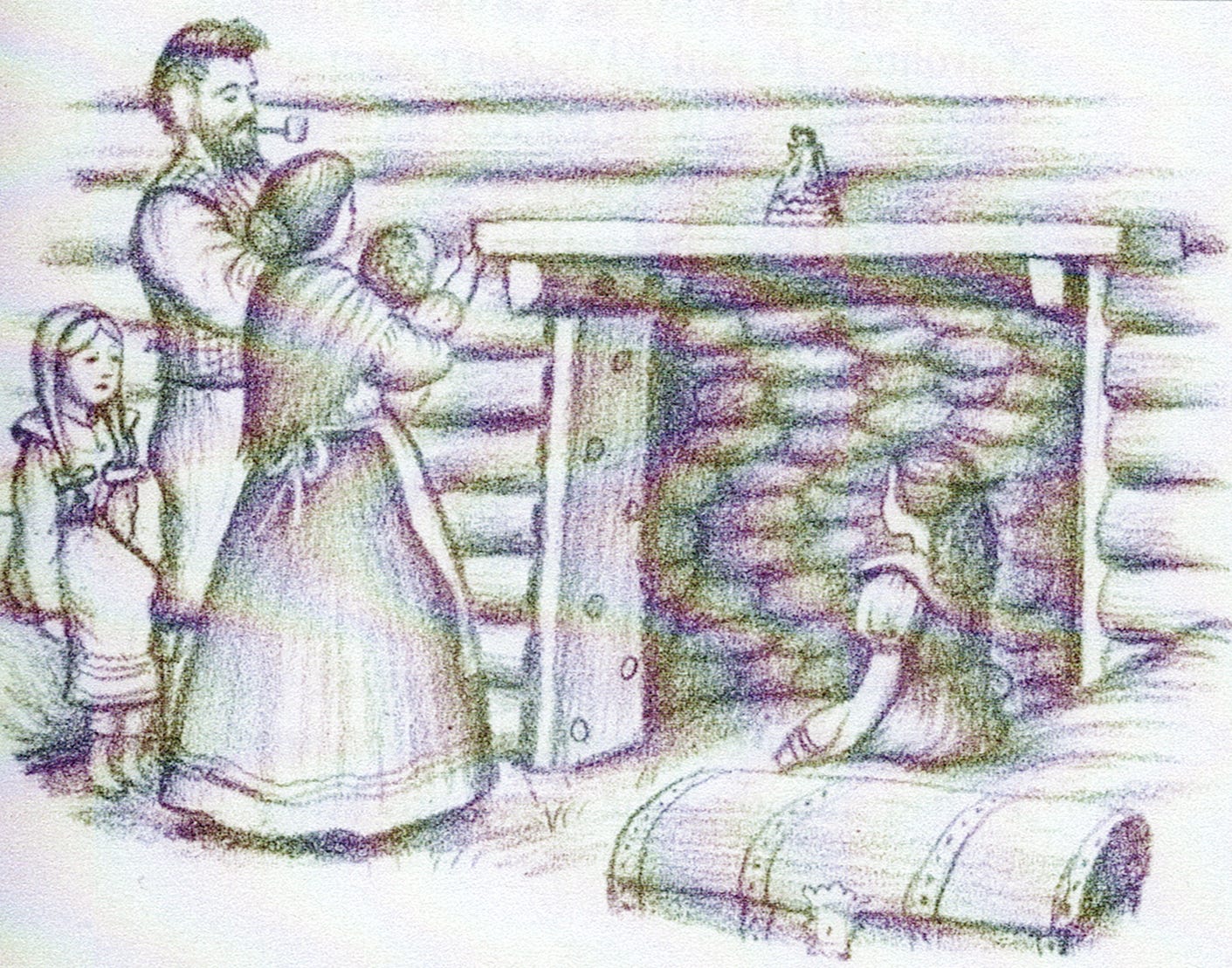

Ma, Pa, Laura and her sisters had nothing, yet Laura was filled with love and contentment. Her parents were literate, mature, brave, loving, satisfied and competent. Her older sister Mary went blind after contracting scarlet fever. Throughout the books are the themes of generosity, of appreciating whatever small luxury was available, and of hard work. The underlying premise is that life is good, and if it isn’t always fair, if the powers that be pound you down, you can always rise up and start again. Optimism pervaded.

At the end of the first volume, Pa is singing and playing his fiddle.

“What are the days of auld Lang Syne, Pa?” Laura asked, when the music stopped.

“They are the days of a long time ago, Laura,” Pa said. “Now go to sleep.”

But Laura lay awake, listening to Pa’s fiddle softly playing and to the lonely sound of the wind in the big woods. She looked at Pa sitting on the bench by the hearth, his brown hair and whiskers as prominent as ever. The firelight glistened on the honey-brown fiddle.

She looked at Ma gently rocking and knitting.

And she thought to herself, “this is now.”

The cozy house, Pa and Ma, the firelight and the music were now, not a long time ago; not auld lang syne.

Laura was in her sixties and seventies when she wrote the books. The world of the twentieth century with its electronic marvels: electricity, movies, , automobiles, skyscrapers, and recorded music, along with the world wars and the Great Depression, was her contemporary reality. But her memory was sweet and green.

If we could get into Laura’s head, it would sound something like this. “I am filled with love, security and contentment. I know that in the future, a long, long time from now, in a faraway place, I will look back and remember this moment. I’ll remember warmth, love and happiness. I’ll wish I were back here with Ma and Pa, the fire and the fiddle. There is nothing more I could possibly want than just being here. And the most wonderful thing of all is that I really am here. It is not the faraway future. This is now.”

Writing in the 1930s and 40s about life in the 1870s and 80s, Laura depicted an idealized, children’s version of her past. But when she uttered those three words, she meant them.

Make no mistake, Laura’s Little House World was no picnic. She and her family endured wolves, locusts, disease, floods, prairie fires, loneliness, isolation, near- starvation and blizzards. During The Long Winter, they were snowed in from October to May; they almost froze to death and were always hungry. At another time their little family sat alone in the midst of a vast plain, listening to the frightening howls of the Indians. Even government bureaucracy forced them off their land. Their lives were surfeited with danger, insecurity, disease, injustice, uncertainty and foreboding. Yet she remembers those times fondly because of her family’s solidarity, strength, warmth, love and positive spirit.

If you find the essays on CRISIS meaningful, interest or even entertaining, please share.

Michael Eisner, the former CEO of Disney, expressed a similar sentiment. “I wish I could keep things the way they are now. I’d like my kids to stay the same age, the job continues just as it’s going. I like my life just the way it is at present.”

Most of our childhoods were far from ideal; life can be messy. But we parents should do our best to fashion a world in which our children awaken at night, look at the firelight and think, “this is now.”

Substack Sidebar

It’s a lovely thought, a goal worth pursuing, but unrealistic for most of us. What percentage of children experienced that “this-is-now-firelight-feeling?” I have no idea. But I do know this: for the last 75 years, measures of social-well-being, particularly for the family, have fallen to tragic lows. The fertility rate in the United States in 2023 was the lowest since 1979. Americans are not reproducing themselves. Between 2007 and 2022 the national birth rate declined by almost twenty-three percent. In 2020, the total fertility rate hit a record low of 1.64, far below the 2.1 level for population stability. During that time, out of wedlock births soared.

In a revealing book, The Day America Told the Truth, James Patterson and Peter Kim, wrote, “The ideal of childhood is ended. A startling percentage of American children actually lose their virginity before the age of thirteen.” They’re losing their childhood, all of their innocence in other ways as well… “The homicide rate among young American males is twenty times that of Western Europe and forty times the Japanese rate.”

They published those findings in 1991. And so it goes today.

Damiel Partick Moynihan, a sociology professor, Democrat Senator from New York, and U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, made the following prescient prediction in 1965.

[The] one unmistakable lesson in American history” is a country that allows “a large number of young men to grow up in in broken families dominated by women, never acquiring any set of rational expectations about the future – that community asks for and gets chaos. Crime, violence, unrest, disorder – most particularly the furious, unrestrained lashing out at the whole social structure – that is not only to be expected; it is very near inevitable.

Sadly, Moynihan was correct

This is now.

Alert! One example of the cultural forces that have been undermining marriage and family has been Cosmopolitan magazine. In next week’s piece, as a public service to the 99.99% of men who have never read the magazine, we’ll take a deep dive into Cosmo.